In the Spotlight

Mental Health Disparities in the Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual, Transgender, or Gender Nonconforming Community

The Impact of Public Policy

By: Carolyn Stroebe, Ph.D.

Good common sense would predict that discrimination against and lack of protection for the Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual; Transgender or Gender Nonconforming (hereinafter “LGBT”[] community have a negative impact on those individuals. The science of psychology has put this notion on solid ground by showing that reducing discrimination by increasing protection is related to more positive outcomes.[]

The problem is urgent and growing given recent changes in public policy[] aimed to decrease the rights of LGBT people: for example, the U.S. Department of Justice has specified that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act does NOT protect lesbian, gay or transgender people, and about 125 state bills restricting the rights of LGBT individuals and their families have been introduced. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has apparently discussed increasing the rights of health care providers to refuse to treat LGBTs due to their religious beliefs. Such changes and threats of such are not only unfair but increase stress among LGBTs.

It is the author’s intention, with this article, to educate the reader about:

- Mental health disparities between LGBTs and their heterosexual and/or cis-gender peers and

- Probable causes and solutions for the discrepancies.

Health Disparities

Although the focus of this article is mental health, there are physical health disparities as well, and the two are often connected. LGBT individuals experience more mental health (and physical health) problems than those who are heterosexual and/or cisgender.[] These vary depending on age and specific orientation.[]

Young gay men or young men who have sex with men have higher rates of HIV diagnoses – and this is particularly true among men of color.[] LGBT youth are more likely to have mental health issues, including substance abuse and more frequent suicide ideation and attempts, and are more likely to smoke and be homeless than others.[]

Mental health and physical health disparities continue into adulthood for older LGBTs and new disparities appear.[] Lesbians and bisexual women appear to use preventative measures such as mammograms or other routine gynecological exams, and tend to become obese more frequently compared with heterosexual women. Higher incidents of breast cancer occur among lesbian and bisexual women, which may be related to higher use of alcohol and smoking.[] Compared with heterosexual women, these two groups also tend to be victims of psychological aggression, physical violence, rape and stalking.[]. Depression is more likely in later adulthood for LGBT individuals.[]

Possible or Probable Causes for the Discrepancies

In an excellent article, using meta-analyses, Ilan H. Meyer[] provides evidence regarding the higher prevalence of mental disorders (e.g., substance use, affective disorders including suicide among lesbians, gay and bisexual individuals. He also provides minority stress as a theoretical framework for these disparities. The author assumes these findings and the theory extend to the entire LGBT community.

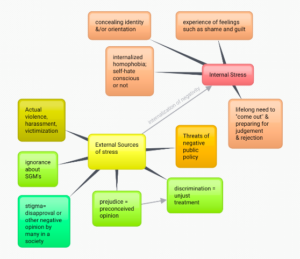

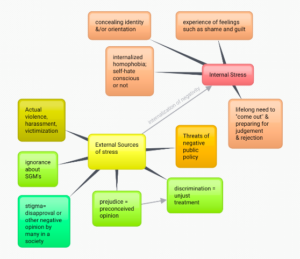

Figure 1 suggests some of the factors that create stress. All of these factors set up a risk of poor mental health outcomes.

Figure 1: External and Internal Factors that Create Stress

Link here for full-size Figure 1.

An LGBT individual is confronted with multiple stressors from society; the most serious of which are actual violence and harassment. Factors such as stigma, prejudice (preconceived opinions about LGBTs) tend to be chronic. Although ignorance about LGBTs by non-LGBTs may not be intentionally harmful, ignorance is hurtful, causing LGBTs to feel misunderstood. Negative public policy and even the threat of such is harmful to LGBTs.

As they live their lives, LGBT individuals internalize this negativity from society as stressors. They develop behaviors that exacerbate the problem – such as concealing their true identities or orientations (which can involve lying to others), or feeling shame and guilt for various reasons (e.g., not meeting the expectations of one’s parents). The mere need to “come out” throughout one’s life, never knowing when one will be rejected, is a constant stressor that can wear a person down. Denial by well-meaning non-LGBTs – that such rejection of and other negative attitude and behaviors towards LGBTs in the 21st century has been eradicated – is also harmful.

Potential Solutions

There are many ways to cope with these stressors, internal and external. The solutions can be internal, i.e., initiated by the individual, or external, e.g., through community action, attitude change in the larger society, or altering public policy. The remainder of this article will focus on the latter, while subsequent articles will consider the former solution categories.

Discriminatory v. Supportive Public Policies: Making a Difference in the LGBT Community

Discriminatory public policy deprives LGBTs of privileges enjoyed by heterosexual or cisgender individuals or fails to protect LGBTs from discrimination, violence or other hate crimes. Naturally this increases stress, and the risk of mental health problems such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, suicidality, and substance use disorders.

Supportive public policies – those aimed at reducing discrimination and extending legal protections to LGBTs (e.g., marriage equality) – are associated with reduced stigma, stress levels, suicidality and better physical and mental health outcomes.

Similar changes in policies in the workplace have similar results. This type of support at work is associated with improved health and increased job commitment, satisfaction and productivity for Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual employees.[], []

The American Psychological Association (APA) recommends legislative, administrative and regulatory solutions that support equality for and eliminate discrimination against the LGBT population, and well as advances in research about health and mental health disparities. Because of this research, the APA has come out to actively support the Equality Act[], which “would amend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other civil rights laws to extend protection against discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation and gender identity in public accommodations, education, employment, housing, credit and the jury system.”[] The poster below most eloquently sums up the data and APA’s position.[]

The author recommends finding ways to educate the general public about the LGBT community and their needs, to increase understanding and acceptance, and decrease the ignorance which can become unintended hurtfulness. A related goal would be to increase cultural competency and sensitivity among professional health and mental health care providers.

PWDF Profile

Who We Are

People With Disabilities Foundation is an operating 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in San Francisco, California, which focuses on the rights of the mentally and developmentally disabled.

Services

Advocacy: PWDF advocates for Social Security claimant’s disability benefits in eight Bay Area counties. We also provide services in disability rights, on issues regarding returning to work, and in ADA consultations, including areas of employment, health care, and education, among others. There is representation before all levels of federal court and Administrative Law Judges. No one is declined due to their inability to pay, and we offer a sliding scale for attorney’s fees.

Education/Public Awareness: To help eliminate the stigma against people with mental disabilities in society, PWDF’s educational program organizes workshops and public seminars, provides guest speakers with backgrounds in mental health, and produces educational materials such as videos.

Continuing Education Provider: State Bar of California MCLE and Commission of Rehabilitation Counselor Certification.

|